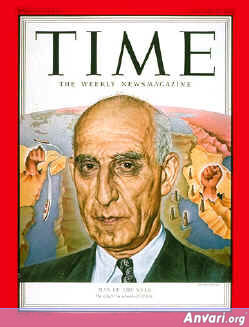

Mohammad Mossadegh

FROM THE TIME ARCHIVE Jan. 7, 1952 Once upon a time, in a mountainous land between Baghdad and the Sea of Caviar, there lived a nobleman. This nobleman, after a lifetime of carping at the way the kingdom was run, became Chief Minister of the realm. In a few months he had the whole world hanging on his words and deeds, his jokes, his tears, his tantrums. Behind his grotesque antics lay great issues of peace or war, progress or decline, which would affect many lands far beyond his mountains. His methods of government were peculiar. For example, when he decided to shift his governors, he dropped into a bowl slips of paper with the names of provinces; each governor stepped forward and drew a new province. Like all ministers, the old nobleman was plagued with friends, men-of-influence, patriots and toadies who came to him with one proposal or another. His duty bade him say no to these schemes, but he was such a kindly fellow (in some respects) that he could not bear to speak the word. He would call in his two-year-old granddaughter and repeat the proposal to her, in front of the visitor. Since she was a well- brought-up little girl, to all these propositions she would unhesitatingly say no. "How can I go against her?" the old gentleman would ask. After a while, the granddaughter, bored with the routine, began to answer yes occasionally. This saddened the old man, for it ruined his favorite joke, and might even have made the administration of the country more inefficient than it was already. In foreign affairs, the minister pursued a very active policy--so active that in the chancelleries of nations thousand of miles away, lamps burned late into the night as other governments tried to find a way of satisfying his demands without ruining themselves. Not that he ever threatened war. His weapon was the threat of his own political suicide, as a willful little boy might say, "If you don't give me what I want I'll hold my breath until I'm blue in the face. Then you'll be sorry." In this way, the old nobleman became the most world-renowned man his ancient race had produced for centuries. In this way, too, he increased the danger of a general war among nations, impoverished his country and brought it and some neighboring lands to the very brink of disaster. Yet his people loved all that he did, and cheered him to the echo whenever he appeared in the streets. The New Menace. In the year of his rise to power, he was in some ways the most noteworthy figure on the world scene. Not that he was the best or the worst or the strongest, but because his rapid advance from obscurity was attended by the greatest stir. The stir was not only on the surface of events: in his strange way, this strange old man represented one of the most profound problems of his time. Around this dizzy old wizard swirled a crisis of human destiny. He was Mohammed Mossadegh, Premier of Iran in the year 1951. He was the Man of the Year. He put Scheherazade in the petroleum business and oiled the wheels of chaos. His acid tears dissolved one of the remaining pillars of a once great empire. In his plaintive, singsong voice he gabbled a defiant challenge that sprang out of a hatred and envy almost incomprehensible to the West. There were millions inside and outside of Iran whom Mossadegh symbolized and spike for, and whose fanatical state of mind he had helped to create. They would rather see their own nations fall apart than continue their present relations with the West. Communism encouraged this state of mind, and stood to profit hugely from it. But Communism did not create it. The split between the West and the non-Communist East was a peril all its own to world order, quite apart from Communism. Through 1951 the Communist threat to the world continued; but nothing new was added--and little subtracted. The news of 1951 was this other danger in the Near and Middle East. In the center of that spreading web of news was Mohammed Mossadegh. |